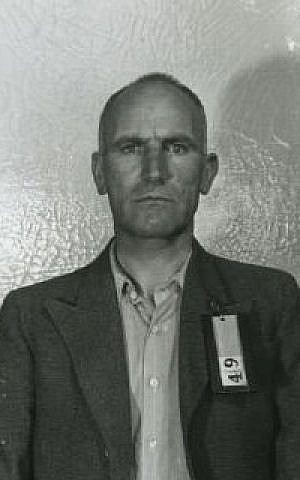

With her ‘satanic hunting instinct,’ the notorious Anna ‘Ans’ van Dijk is fingered to have tipped off Nazis about the Jews hidden in the ‘Secret Annex,’ leading to their murders

Anne Frank may have been betrayed by the infamous Nazi collaborator Anna “Ans” van Dijk, a Jewish woman who agreed to help capture other Jews in hiding in exchange for her freedom.

In his new book, “The Backyard of the Secret Annex,” author Gerard Kremer claims that van Dijk was responsible for betraying Anne and seven other Jews in hiding behind an Amsterdam office building. According to Kremer, his late father — also named Gerard Kremer — occasionally spotted van Dijk during her visits to a Nazi office building where Kremer worked during the war. There, she supposedly met with handlers and made phone calls.

The book’s major claim is that Kremer, who died in 1978, overheard van Dijk speaking about Jews who were in hiding on the Prinsengracht, the canal where Anne’s so-called “Secret Annex” was located. The conversation allegedly took place at the beginning of August, just days before the Nazis raided the annex on August 4, 1944.

Of the eight Jews in hiding, only Otto Frank survived the Holocaust.

This is not the first time van Dijk has been named as a suspect in the betrayal of Anne Frank. As the only woman executed by Dutch authorities for collaborating with the Nazis, her name has been associated with the diarist’s arrest for decades.

In the 1960s, when Dutch police conducted an investigation into the arrest of Anne and the other Jews, it was noted that van Dijk had betrayed two Jews who were in hiding close to the “Secret Annex.” Reportedly, her tip-off was received just a day or two before the Nazis arrested the eight Jews hidden behind Otto Frank’s office building.

It is possible van Dijk tapped into a network of people that led her to the Prinsengracht 263. In her book, “The Hidden Life of Otto Frank,” author Carol Ann Lee pointed out that van Dijk’s “handler” — the Dutch Nazi Peter Schaap — was responsible for the arrest of Hendrik van Hoeve, who had covertly supplied the annex with groceries.

‘The simple Jewish lesbian’

Born to Jewish parents, Ans van Dijk married a man named Bram Querido in 1927. The partnership lasted for eight years, at which point van Dijk set up shop with a woman named Miep Stodel.

Before the war, van Dijk opened a hat store in Amsterdam — called Maison Evany — in which she employed Stodel. The couple shared an apartment above the shop. Van Dijk remained under-the-radar until 1941, when her business was closed as part of the Nazi occupiers’ anti-Jewish laws. Shortly afterwards, her lover fled to Switzerland.

As the Nazis started to deport Jews from the city, van Dijk initially helped the resistance by supplying her fellow Jews with hiding places, identity papers, and necessities. In the process of making these connections, she went into hiding herself. On Easter in 1943, however, she was betrayed and arrested along with other Jews.

Fortuitously for her own survival, van Dijk was captured by Nazi security police detective Peter Schaap, a man who is said to have recognized something in van Dijk’s demeanor. Schaap offered her freedom in exchange for her help in capturing other Jews in hiding. Van Dijk accepted the offer, which in addition to sparing her life, included cash incentives.

“[She] was the best of the 10 who worked for me at the time,” said Schaap of van Dijk after the war. During her first weeks on the job, van Dijk betrayed nine Jews, including her own brother, his wife, and their three children.

Going by a fake name, the cunning van Dijk convinced dozens of Jews that she sought to help them. Instead, she betrayed their hiding places to Schaap, who in turn had the Jews arrested. Among her strategies, van Dijk maintained a “trap house” close to Anne Frank’s childhood home in the River Quarter, for the purpose of ensnaring unsuspecting Jews.

By the end of the war, more than 100,000 Dutch Jews had been deported to Nazi death camps and murdered.

Within a couple of months of making her arrangement with Schaap, van Dijk found herself at the head of a group of women who were hunting Jews. According to historian Koos Groen, this promotion had a profound impact on the Nazi collaborator.

“[Van Dijk] was in any case of more than mediocre intelligence but also suffered from a lack of self-confidence,” wrote Groen. “She compensated for this by wanting to be ‘the best in the class.’ …Schaap complimented her again and again. That felt pleasant for a woman who was rarely or never praised in her life. It must have given her a sense of power, a feeling that the simple Jewish lesbian had never known before,” wrote Groen.

‘A satanic hunting instint’

After the war, van Dijk moved to The Hague, where she was arrested at a girlfriend’s home on June 20, 1945. Charged with 23 counts of treason, van Dijk appeared before a special court in Amsterdam and confessed to all the counts against her.

During her trial, van Dijk admitted to helping the Nazis capture at least 145 Jews, including her relatives. According to some estimates, she and the “hunters” she managed were responsible for the capture of as many as 700 Jews. The prosecutor famously accused van Dijk of having “a satanic hunting instinct,” and an ex-lover referred to her as “a devil in human form.”

In her defense, van Dijk told the special court she had acted out of self-preservation and “wild fear.” Despite her pleas, the collaborator was sentenced to death. She filed appeals with the court and the Queen, both of which were denied.

On January 14, 1948, van Dijk was executed by a firing squad of 12 in Amsterdam. The day before, she had been baptized and joined the Roman Catholic Church in a final, desperate attempt to save her life. The 42 year old was given an anonymous burial.

According to Groen, discrimination was at play when Dutch officials chose to execute the Jewish van Dijk, as opposed to other people — including women — who had committed similar crimes and were let off the hook with light jail sentences.

“People were naturally bombarded with anti-Semitic propaganda for five years,” wrote Groen. “Second, [van Dijk] was a lesbian. That was totally unspeakable at that time. That ‘abnormal’ relationship was found dirty and placed her on the margins of society,” wrote Groen, who added that van Dijk’s homely appearance did not help her cause.

According to Groen, “No matter how crazy it may sound: [van Dijk’s] behavior gave her security by the certainty that as long as she was useful to Schaap, she . . . had a real chance of survival.

“Naturally it was not about a luxury life, but about survival. Because man is the only animal that knows that he will die,” wrote Groen.

For biographer Carol Ann Lee, the resurfacing of Ans van Dijk as a suspect in the betrayal of Anne Frank is not surprising. In the author’s assessment, however, a more likely suspect is Tony Ahlers, a shadowy figure who blackmailed Otto Frank for years.

“I’m very much looking forward to Vince Pankoke’s findings on the subject,” Lee told The Times of Israel, referring to a high-profile investigation being conducted into the Nazis’ raid on the annex. Led by former FBI agent Pankoke and no fewer than 19 forensics experts, the inquiry’s findings will be released on August 4, 2019 — the 75th anniversary of Anne Frank’s arrest.

“What I find most interesting of all is the fact that we are still discussing and researching the identity of the betrayer after so many theories have already been put forward,” said Lee.

“I think, more than anything, that shows how important Anne’s diary has been and continues to be for all of us,” said the biographer. “It does indicate too that people are keen to see justice is done insofar as it can be now — even if simply by putting a name to the person who committed such an unimaginably terrible act,” said Lee.